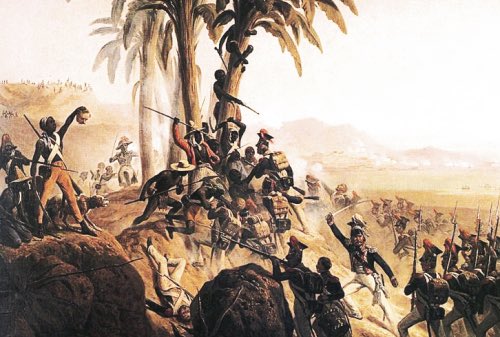

One of the most notable aspects of Haitian history is that the nation is the only one to have emerged as the result of a successful slave rebellion. From 1791 through 1804, enslaved people and their allies in Saint-Domingue fought a protracted revolution to win their independence from France. This was not the first episode of rebellion or fear of rebellion, as the case of François Makandal shows, but it was the most successful. After a ceremony at Bois Caïman, the rebellion began in August 1791. Within a few weeks, the insurrection grew to include more than one hundred thousand participants who destroyed hundreds of plantations. – Source

Bois Caïman (Haitian Creole: Bwa Kayiman) is the site of the Vodou ceremony during which the first major slave insurrection of the Haitian Revolution was planned. On the night of August 14, 1791, 300 representative slaves from nearby plantations gathered to participate in a secret ceremony conducted in the woods by nearby Le Cap in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Presided over by Dutty Boukman, a Haitian slave leader born in Jamaica. The ceremony served as both a religious ritual and strategic meeting as conspirators met and planned a revolt against the ruling white planters of the colony’s wealthy Northern Plain.

- Below I posted a few of the dates from Haitian revolution written by Kona Shen at Brown University Department of Africana Studies but click here for the complete timeline and much more on Haiti’s History on their site.

- 16 August 1791: Slaves in the Limbé district stray from the leaders’ plan, apparently due to a misunderstanding, and are caught setting fire to an estate. During their interrogation, they reveal the conspiracy and the names of the leaders. Interestingly, though, many of the planters who are warned of the rebellion stand by their slaves and refuse to believe the rumors. One plantation manager, for example, “offered his own head in exchange if the denunciations….proved true.” Other planters, warned of the coming violence, escaped with their lives but still couldn’t protect their property, often losing everything.

The other slaves involved in the conspiracy prepare to move ahead with the rebellion as planned, vowing to “to burn le Cap, the plantations, and to massacre the whites all at the same time.”

22 August 1791: The slaves launch their insurrection in the North. That night Boukman and his forces march throughout the region, taking prisoners and killing whites. By midnight, plantations are in flames and the revolt has begun. Armed with torches, guns, sabers, and makeshift weapons the rebels continue their devastation as they go from plantation to plantation. By six the next morning, only a few slaves in the area have yet to join Boukman, and scores of plantations and their owners are destroyed.

The group, numbering 1,000 to 2,000, next splits into smaller bands to attack designated plantations, demonstrating their highly organized strategy. As the revolt in the North grows “awesome in dimensions,” whites become anxious about defending Le Cap, where the colonial government is centralized. It is to Le Cap – the social and cultural hub of the colony – that whites flee their burning plantations and rebelling slaves. Later an interrogated slave would declare that “in every workshop in the city there were negroes concerned in the plot.” The whites and slaves both realize that controlling the city would be critical in determining the revolution’s outcome.

Blanchelande writes that “Fears of a conspiracy [in Le Cap] were confirmed as we had successfully discovered and continue daily to discover plots that prove that the revolt is combined between the slaves of the city and those of the plains; we have therefore established permanent surveillance to prevent the first sign of fire here in the city which would soon develop into a general conflagration.”

23 August 1791: The slaves march to the Limbé district, adding to their forces. The group moves from plantation to plantation, seizing control and establishing military camps. Along the way more slaves join the rebellion, and those who don’t are cut down mercilessly.

By the end of the day, “the finest sugar plantations of Saint-Domingue were literally devoured by flames.” A horrified colonist wrote that “one can count as many rebel camps as there were plantations.”

24 August 1791 : The slaves continue west to Port-Margot in the early evening, hitting at least four plantations.

The rebels march to Le Cap, after burning down the region’s largest plantations and killing scores of whites. Every entrance to the city is guarded, and the slaves march against the whites’ cannons and guns, meeting armed resistance for the first time. Though the whites manage to drive the slaves back, the rebels divide up and regroup, returning by two different routes to successfully seize the city.

The slaves hold out for three weeks against the planters, who are badly armed, disorganized, injured, and desperately in need of help. The slaves’ strategy is clear: every time the planters circle or overcome them, the slaves retreat to the mountains to reorganize and prepare a new attack.

25 August 1791: At the same time, slaves in the northeast rise up, “torch in hand, with equal coordination and purpose,” and advanced “like wildfire.” The slaves burn down the plantations methodically until all the major parishes in the upper North Plain region are hit and communication between them is severed.

Click Here to continue reading the timeline.

![Sunday On Chad’s Instagram! 😩😂🇭🇹

[ See Our Previous Post ]

🎥 @ochocinco

#lunionsuite #haitianamerican #haitian #chadochocinco](https://scontent-yyz1-1.cdninstagram.com/v/t51.75761-15/486064093_18500558206023307_3804672392637993767_n.jpg?stp=dst-jpg_e35_tt6&_nc_cat=106&ccb=1-7&_nc_sid=18de74&_nc_ohc=WoAPC1t_7cUQ7kNvgGv0HH4&_nc_oc=AdkO8pwYMdEH98JcDXdVLRYB4d-pfoKlTjf2-RqK-5Y1LMkt0xWne6JRJevr1o611jY&_nc_zt=23&_nc_ht=scontent-yyz1-1.cdninstagram.com&edm=AM6HXa8EAAAA&_nc_gid=JkAt6b6QbGY58bzi3_Z4ww&oh=00_AYHAlnHyX6LFSQYjsE_radVKq7bKrSeWrR0nR30myC9dOA&oe=67E898FB)