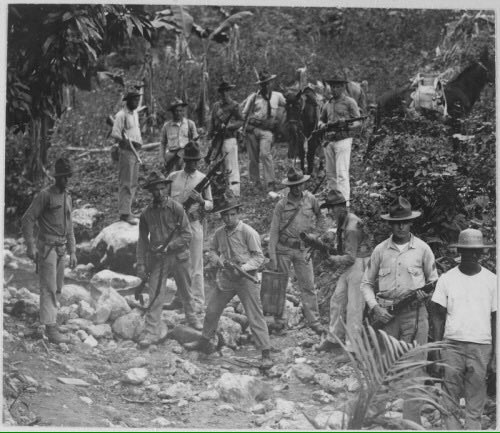

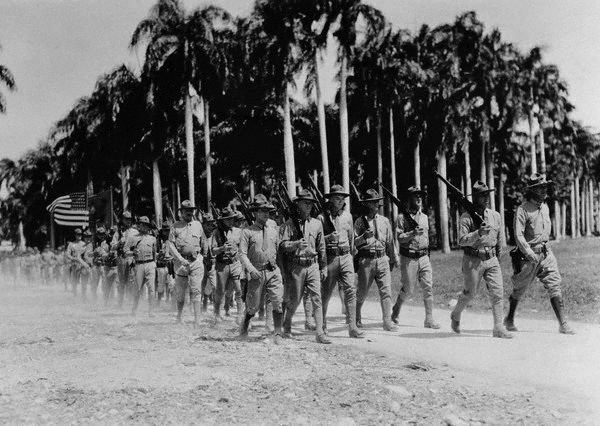

A century ago, American troops invaded and occupied a foreign nation. They would stay there for almost two decades, install a client government, impose new laws and fight insurgents in bloody battles on difficult terrain. Thousands of residents perished during what turned out to be 19 years of de facto U.S. rule. The country was Haiti, the Caribbean nation that’s often seen by outsiders as a metaphor for poverty and disaster. Yet rarely are Americans

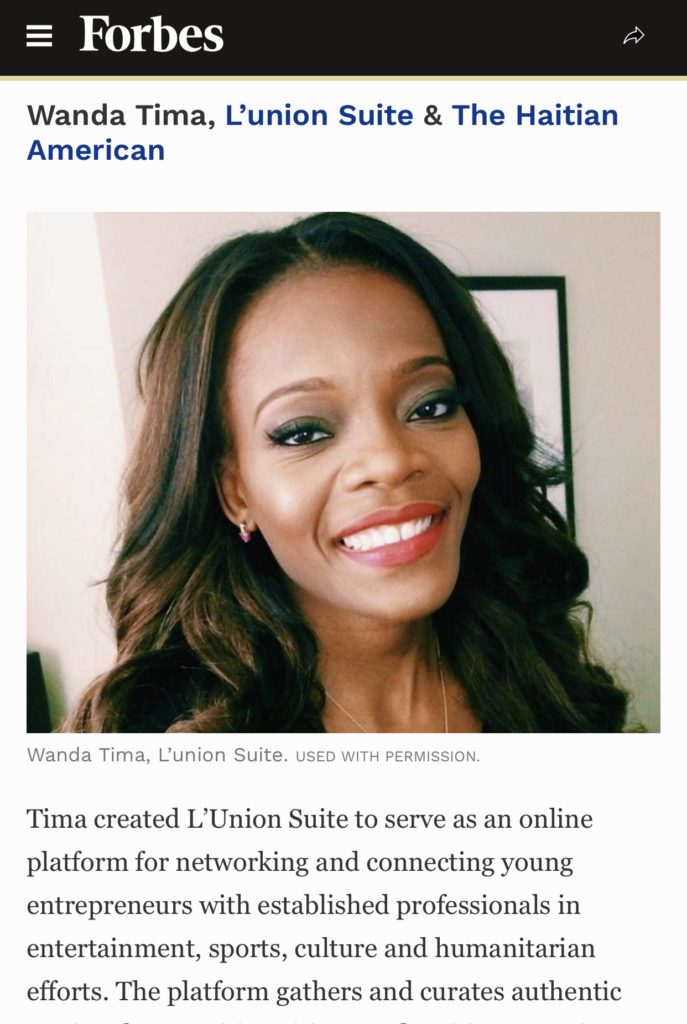

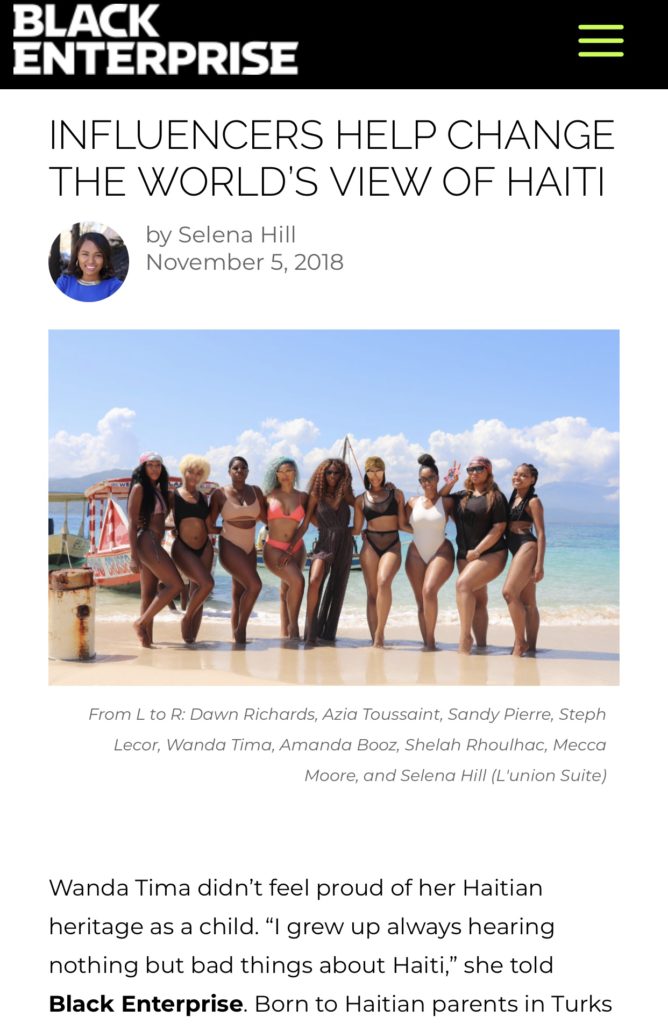

The country was Haiti, the Caribbean nation that’s often seen by outsiders as a metaphor for poverty and disaster. Yet rarely are Americans confronted with their own hand in its misfortunes. – Read More Washington Post

Below are a few excerpts from different articles about the occupation and feel free to research more on your own.

Office of Historian : Following the assassination of the Haitian President in July of 1915, PresidentWoodrow Wilson sent the United States Marines into Haiti to restore order and maintain political and economic stability in the Caribbean. This occupation continued until 1934.

The United States Government’s interests in Haiti existed for decades prior to its occupation. As a potential naval base for the United States, Haiti’s stability concerned U.S. diplomatic and defense officials who feared Haitian instability might result in foreign rule of Haiti. In 1868, President Andrew Johnson suggested the annexation of the island of Hispaniola, consisting of Haiti and the Dominican Republic, to secure a U.S. defensive and economic stake in the West Indies. From 1889 to 1891, Secretary of State James Blaine unsuccessfully sought a lease of Mole-Saint Nicolas, a city on Haiti’s northern coast strategically located for a naval base. In 1910, President William Howard Taft granted Haiti a large loan in hopes that Haiti could pay off its international debt, thus lessening foreign influence. The attempt failed due to the enormity of the debt and the internal instability of the country.

France, as the former colonizer of Haiti, retained strong economic and diplomatic ties with the Haitian Government. In the 1824 Franco-Haitian Agreement, France agreed to recognize Haitian independence if Haiti paid a large indemnity. This kept Haiti in a constant state of debt and placed France in a position of power over Haiti’s trade and finances.

Although unhappy about the Haitians’ close connection to France, the United States became increasingly concerned with heightened German activity and influence in Haiti. At the start of the 20th century, German presence increased with German merchants establishing trading branches in Haiti that dominated commercial business in the area. German men married Haitian women to get around laws denying foreigners land ownership and established roots in the community. The United States considered Germany its chief rival in the Caribbean and feared German control of Haiti would give them a powerful advantage in the region.

As a result of increased instability in Haiti in the years before 1915, the United States heightened its activity to deter foreign influence. Between 1911 and 1915, seven presidents were assassinated or overthrown in Haiti, increasing U.S. policymakers’ fear of foreign intervention. In 1914, the Wilson administration sent U.S. Marines into Haiti. They removed $500,000 from the Haitian National Bank in December of 1914 for safe-keeping in New York, thus giving the United States control of the bank. In 1915, Haitian President Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam was assassinated and the situation in Haiti quickly became unstable. In response, President Wilson sent the U.S. Marines to Haiti to prevent anarchy. In actuality, the act protected U.S. assets in the area and prevented a possible German invasion. Read More : Office of Historian

The New Yorker by Haitian Writer Edwidge Danticat,

On July 28, 1915, United States Marines landed in Haiti on the orders of President Woodrow Wilson, who feared that European interests might reduce American commercial and political influence in Haiti, and in the region surrounding the Panama Canal. The precipitating event was the assassination of the Haitian President, Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, but U.S. interests in Haiti went back as far as the previous century. (President Andrew Johnson wanted to annex both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Twenty years later, Secretary of State James Blaine unsuccessfully tried to obtain Môle-Saint-Nicolas, a northern Haitian settlement, for a naval base.)

By 1915, the Americans were also afraid that an ongoing debt Haiti was forced to pay to France tied the country too closely to its former colonizer; Germany’s growing commercial interests in Haiti were another major concern. So one of the first actions carried out by the U.S. at the start of the occupation was to move Haiti’s financial reserves to the United States and then rewrite its Constitution to give foreigners land-owning rights.

There is a commemorative banner near the site of the 1929 massacre acknowledging the day—something to show that the town remembers. But it is very hard to figure out what to commemorate, what to remember and what to forget, during a nineteen-year occupation.

There is a commemorative banner near the site of the 1929 massacre acknowledging the day—something to show that the town remembers. But it is very hard to figure out what to commemorate, what to remember and what to forget, during a nineteen-year occupation.

In my own family, there were many stories. My grandfather was one of the Cacos, or so-called bandits, whom retired American Marines have always written about in their memoirs. They would be called insurgents now, the thousands who fought against the occupation. One of the stories my grandfather’s oldest son, my uncle Joseph, used to tell was of watching a group of young Marines kicking around a man’s decapitated head in an effort to frighten the rebels in their area. There are more stories still. Of the Marines’ boots sounding like Galipot, a fabled three-legged horse, which all children were supposed to fear. Of the black face that the Marines wore to blend in and hide from view. Of the time U.S. Marines assassinated one of the occupation’s most famous fighters, Charlemagne Péralte, and pinned his body to a door, where it was left to rot in the sun for days.

The notion that there were indispensable nation-building benefits to this occupation falls short, especially because the roads, schools, and hospitals that were built during this period relied upon a tyrannical forced-labor system, a kind of national chain gang. Call it gunboat diplomacy or a banana war, but this occupation was never meant—as the Americans professed—to spread democracy, especially given that certain democratic freedoms were not even available to the United States’ own black citizens at the time. “Think of it! Niggers speaking French,” Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan said of Haitians. – Continue Reading Here

There is certainly a lot to know about this issue.

I like all the points you have made.

It’s awesome to go to see this site and reading the views of all colleagues concerning this article, while I am also keen of

getting knowledge.

However the issue using this approach is the fact that you will waste

considerable time. Without a genuine Clash Royale hack strategy, you will spend many more hours

trying to unlock silver, gems and cards.