Photos by Katie Orlinsky for Al Jazeera America

“Lesbian and gay people are beaten in the street, on the way to school. They are discriminated against by health professionals, abandoned by their families,” said Dave Stephen, operations director at SEROvie. “They hide themselves, even though it’s not criminal.”

Haiti’s LGBT community, which has long existed in relative secrecy, has faced greater criticism since the deadly earthquake that struck the island nation in 2010. From the pulpit and on the radio, evangelists, some inspired by American sponsors and mentors, have blamed the earthquake on the sins of the country’s gay population. Gay Haitians living in tent camps after the disaster reported “corrective” rape and increased harassment as a result of the greater exposure of displacement and flimsy shelters.

[Repost from Projects Aljazeera] The courtyard, tucked off a quiet road here and ringed by mango trees heavy with immature green fruit, was bedecked with a rainbow of balloons. One proclaimed “Happy Valentines Day!” though it was May. Another advertised specials at the fast-food chain Red Robin, while a third was imprinted with the Whole Foods logo. There is no Red Robin or Whole Foods in Haiti, but the energy in the courtyard of SEROvie, Haiti’s best-known LGBT health organization, had the flavor of an American gay-pride parade.

Beats blared from speakers as Ralph (who requested that his real name be withheld) slunk onto the makeshift concrete catwalk, a space cleared between mismatched chairs crammed mostly with flirting 20-somethings in bright party outfits. Statuesque in sparkly black stilettos and a red velour unitard, Ralph twirled, jutted his hips and flipped the tresses of his long black wig.

“You better work, bitch!” he mouthed, as onlookers laughed, squealed, took selfies and applauded wildly.

For all the raucous festivities bubbling over the high walls of the compound, the day had started on a somber note. It was the International Day Against Homophobia; before delineating the catwalk, organizers had arranged chairs in rows under an awning, where a smaller crowd had listened that morning to speakers discuss the state of rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in Haiti.

“Lesbian and gay people are beaten in the street, on the way to school. They are discriminated against by health professionals, abandoned by their families,” said Dave Stephen, operations director at SEROvie. “They hide themselves, even though it’s not criminal.

”

Haiti’s LGBT community, which has long existed in relative secrecy, has faced greater criticism since the deadly earthquake that struck the island nation in 2010. From the pulpit and on the radio, evangelists, some inspired by American sponsors and mentors, have blamed the earthquake on the sins of the country’s gay population. Gay Haitians living in tent camps after the disaster reported “corrective” rape and increased harassment as a result of the greater exposure of displacement and flimsy shelters.

And last year, more than 1,000 people participated in a march against homosexuality in Port-au-Prince organized by a new anti-gay “coalition of moral and religious organizations.” The protest was blamed for an escalation in violence against gay people: Forty-seven attacks were reported in the week surrounding the event, according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Some say a new gay-rights organization Kouraj (“courage” in Haitian Creole), and its brash demands for rights, helped to prompt the backlash.

Now, the fight over gay rights in Haiti has become one that’s largely over visibility. The question of how closeted gays should be is the subject of internal struggles for many gay Haitians, the root of infighting among advocates and part of a broader societal struggle over what behavior is to be permitted in public.

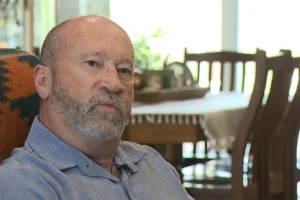

“What we call masisi [Creole for ‘homosexual’] — it’s recently we allow this in public; before it was private,” said pastor Gerard Forges, an organizer of the anti-gay march last year. He said the march was in protest of public displays of homosexuality, not homosexuality itself. Forges emphasized that there are gays in his 7,600-member Pentecostal congregation. To him, it is not the people themselves who are the problem, but their actions. “We have homosexuals in church; we sit with them; we say, ‘God loves you, we love you, but we don’t like what you do.’”

Forges’ family lives between Port-au-Prince and Georgia. He holds a divinity degree from Jacksonville University in Florida and is pursuing a doctorate from Oral Roberts University. He said his organization does not have international funding but that American missionaries visit. “In the U.S. they can’t make public opinion on this subject. There are pastors that agree with me, but they can’t do anything this public. They encourage me, tell me to keep my stance.”

– Continue Reading here [Repost from Projects Aljazeera]