by Celucien L. Joseph, PhD

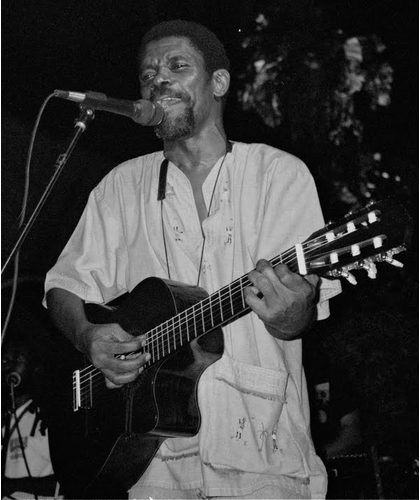

Haiti has lost one of the most important human rights advocates, freedom fighters, public intellectuals, and anti-dictator and American Empire thinkers in the second half of the twentieth-century. Emmanuel Charlemagne (1948-2017) was a political activist and gifted musician who sang boldly the resilience and hope of the Haitian people in the midst of political tragedy and despair, cultural alienation, and imperial interruptions.

As a young man growing up in Haiti, it was through Manno’s musical lyrics that I learned about America’s hegemony in the world and the danger of the American empire, and global capitalism. I learned about the corruption, abuses, and false promises of Haitian government. Manno also taught me about the long-suffering and courage of the Haitian people; through his lyrics, I became aware of the importance of democracy and justice, and the ethics of individual responsibility and collective mobilization toward human flourishing and the common good in the Haitian society. Consider the following verse from the album “La Fimen” (The Smoke) (1994), in which Manno laments about the state of the Haitian society and failure of the Haitian state after 200 years of independence:

Dwa de lòm se konsa l rele

Lamayòt pou ti moun fronte

Apre 200 zan sa n regle

Nèg vle fè n konnen ke solèy se Bondye

Men dyab la ap vini pa pale

Labib son w bagay ki sakre

Yon patay ki pa byen regle

Blan yo pran tè ya

Yo bann bib la n aksepte tande

Correspondingly, as an anti-colonial thinker, Manno confronts white supremacy and colonization with poetic rigor and aggressiveness: “Blan yo pran tè ya /Yo bann bib la n aksepte tande.” The white man took the land and gave us the Bible, and he forced it upon us.

In his revolutionary song, “Oganizasyon Mondyal,” Manno denounces the global class systems and the dominant class that exploits the underclass and mistreats the wretched of the earth. Not only, Manno makes a clarion call to the people (“Lè pèp anba zam tout peyi tout kote”) revolt against the various groups, forces, and institutions that oppress the poor and common people, he informs us the goal of the dominant class is to destroy and kill.

Laklas dominant entelijan ke l ye

An prensip konnen ke l an minorite

L konn ki jan pou l jwe

Pozisyon de klas li se sa ki konte

La fè lenposib la kraze la brize

Pou l elimine ti moun ki lan ze

Nap goumen jouk mayi mi jouk tan nou libere

Pran konfyans lan lit lòt pèp yo ki pa pè tonbe

Delivrans yo se jefò yo lan san ki ap koule

Grenn doktè ta vle preskri yo voye sa jete

For Manno, the Haitian people must continue to fight until they all become free, yet their freedom is in their shed blood. Freedom is costly, and liberty demands the collective sacrifice of the people. Through his revolutionary songs, Manno spoke about the predicament of the Haitian poor and working class and defended their right of existence and freedom, and correspondingly, their right to work and harvest the fruit of their own labor. He awakened the consciousness of the Haitian Youth in the second half of the twentieth-century. I was young (perhaps 9 or 10 yrs. old) and did not understand fully all you were singing about, but somewhat I understood that you were speaking truth, beauty, justice, and love, and the power to the Haitian people and self-agency for the Haitian poor and oppressed class. In “Banm Yon Ti Limyè” (1990), Manno’s cri de coeur for justice, equality, and a better life for all Haitians challenge the powers and political authorities that sustain the suffering and domination of the Haitian people:

Ban m yon ti limyè mèt

Ban m yon ti limyè pou m wè sa k’ap pase

Ban m yon ti limyè mèt

Ban m yon ti limyè souple pou m ka wè

&

Poukisa se nèg yo fè soufri

Poukisa se nèg yo fè sòt

Poukisa nèg paka manje

Poukisa yo mande lanmò

In this lyric, Manno is in the search to find light (limyè) or to be enlightened about the living conditions of black people in the world. He articulates the international suffering and plight of black people in a series of provocative questions:

Why are the black people suffering?

Why can they find food?

Why are they asking for death?

Manno: You championed the cause of the Haitian poor and oppressed, and the victims of the Duvalier regime and Haitian bourgeoisie and political elite class. You advocated total justice in the Haitian civil and political society. You portrayed yourself as the voice for the voiceless and through your songs, you raised the Haitian consciousness about the plight of the Haitian people and underrepresented Haitian families, and the miscarriage of justice in our society and in the world.

Manno: You were also my historian; from you, I became acquainted with a host of Haitian freedom fighters, both Haitian men and women, and was aware of the infinite worth of our glorious Haitian revolution and national heroes and heroines, and the imperative for us to plan collaboratively our future and destiny, and to live together as a people and as a nation.

May you never die in the hearts of the Haitian people!

May the Haitian soul never forget your revolutionary songs of freedom and justice you wrote on their behalf!

Ban m yon ti limyè souple

Ban m yon ti limye tonè

Ban m yon ti limyè

Celucien L. Joseph (PhD, University of Texas at Dallas) is an Assistant Professor of English at Indian River State College. His recent book includes Thinking in Public: Faith, Secular Humanism, and Development in Jacques Roumain (Pickwick Publications, 2017); he is the general editor of the forthcoming text, Between Two Worlds: Jean Price-Mars, Haiti, and Africa (Lexington Books, February 2018).