Hailed as the first professional African-American and Native-American sculptor, Mary Edmonia Lewis had little training but

Hailed as the first professional African-American and Native-American sculptor, Mary Edmonia Lewis had little training but  overcame numerous obstacles to become a revered and respected artist.

overcame numerous obstacles to become a revered and respected artist.

Little is known about her early life. Elusive when it came to personal details, Lewis claim

ed different years of birth throughout out her life, but research seems to indicate she was born around 1844 in upstate New York. Following a childhood that saw her roam the woods with Chippewa Indians, Lewis found her way to Oberlin College in Ohio, thanks to, it seems, the support and encouragement of a successful older brother. Oberlin was a hot bed for the abolitionist movement, a facet of school life that did not escape Lewis and would greatly influence her later work. In addition, Lewis’s time at the college was marked by her emergence as a talented drawer.

But life at Oberlin came to a violent end when Lewis was falsely accused of poisoning two white classmates. Captured and beaten by a white mob, Lewis recovered from the attack and then escaped to Boston, Massachusetts, after the charges against her were dropped.

In Boston, Lewis befriended abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and sculptor Edward A. Brackett. It was Brackett who taught Lewis sculpture and helped propel her to set up her own studio. By the early 1860s, her clay and plaster medallions of Garrison, John Brown and other abolitionist leaders had given her a small measure of commercial success.

In 1864, Lewis created a bust of Colonel Robert Shaw, a Civil War hero who had died leading the all-black 54th Massachusetts Regiment. This was her most famous work to date and the money she earned from the sale of copies of the bust allowed her to move to Rome, Italy—home to a number of expatriate American artists, including several women.

Life in Rome

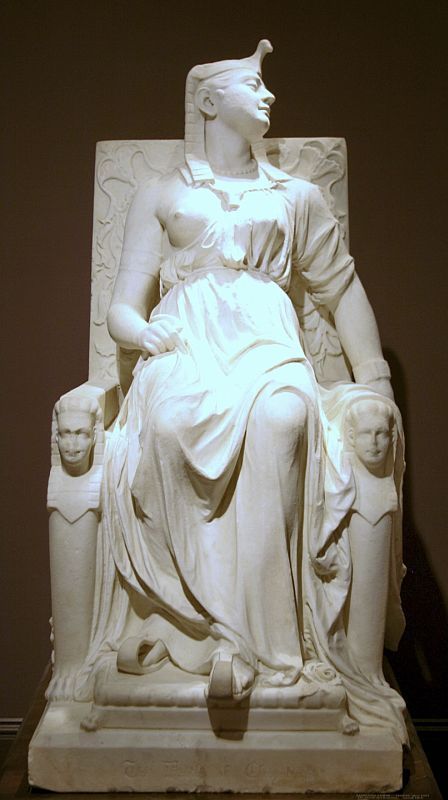

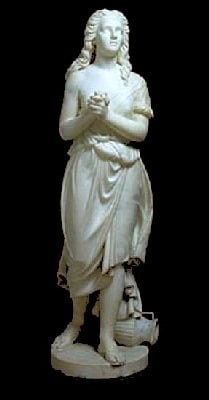

In Italy, Lewis continued her artistic ascendency. Her work over the next several decades moved between African-American themes to work influenced by her devout Catholicism.

n of the Egyptian Queen Cleopatra, titled “The Death of Cleopatra.” Met with critical acclaim when she showed it at the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876 and in Chicago two years later, the two-ton sculpture never returned to Italy with its creator because Lewis couldn’t afford the shipping costs. It was placed in storage and only really rediscovered several decades after her death.Final Years

In recent decades, however, Lewis’s life and art has received well-deserved respect. Her pieces are now part of the permanent collections of the Howard University Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.